There's nothing special about either name though, and your project might have a different first-branch-name. Technically these remote-tracking names are in a separate namespace, too, but we won't go into that here.ģThe old standard, automatic first branch name was master GitHub changed theirs to main and many have followed. :-)ĢYou can make Git use something other than origin here, but that's the default and hence what you are seeing. Since all of them have various flaws, few servers actually seem to make a lot of use of these-but I have no direct insight into how GitHub, Bitbucket, and GitLab run their services, so maybe they do use them and they work better than I think. In any case, this is why remote branch is such a poor phrase: does it mean develop on the other Git? Does it mean origin/develop in your own Git repository?ġThere's a set of facilities in Git, none of which seem quite satisfactory to me, for keeping various hidden names on Git servers. That's why your origin/develop is a remote-tracking name.

#Checkout a remote branch update#

If they did update their develop, you will get any new commits from them, and your Git will update your origin/develop to track the update to their develop. So when you're wondering did they update their develop? that's when you would run git fetch. In between git fetch-es that you run, their develop could be updated, and you won't know. Your Git will see if their Git repository has changed the commit hash IDs stored in their branch names, and if so, will update your remote-tracking names: your origin/develop will update to remember where their develop is now. If they do, your Git will bring over their new commits. Later, you'll run git fetch-or have git pull run git fetch for you-and your Git call call up their Git to see if they have new commits in their repository. I call these remote-tracking names, leaving out the badly overloaded word branch, but still with the somewhat overloaded tracking part.) Parts of Git refer to things like origin/develop as a remote-tracking branch name. The upstream setting of a branch is just one of the various names in your repository, such as the origin/ version of the same name. Your local branch is said to track its upstream. (Parts of Git refer to this as tracking, which is another badly overloaded word. Last-as the final step of git clone-your Git effectively runs git checkout or git switch to create one new local branch, typically master or main, 3 with its upstream set to the origin/ version of that name, which your Git copied from the other Git's un-prefixed version of that name. Your Git sticks origin/ 2 in front of each name. Then, your Git takes each of their branch names, such as develop, and renames them. So, when you clone some Git repository from GitHub or Bitbucket or GitLab or whatever, your Git gets all their Git's commits. Other, non- branch names do the same thing, so non-branch names are just as good as branch names, with one particular exception: checking out a non-branch name results in a detached HEAD. Any branch names just let you-and Git-find certain hash IDs. The commits themselves have big ugly hash IDs, which are how Git actually looks them up in its big database of all-Git-objects. It's the commits, not the names, that matter. What you and the other Git repository share are the commits. When you clone a Git repository, you get all of its commits and none of its branch names.

Their names are theirs, and your names are yours. You can view any other Git's names-those it will show you, that is 1-and copy them to your own Git repository if you like, but your copies are yours, not theirs.

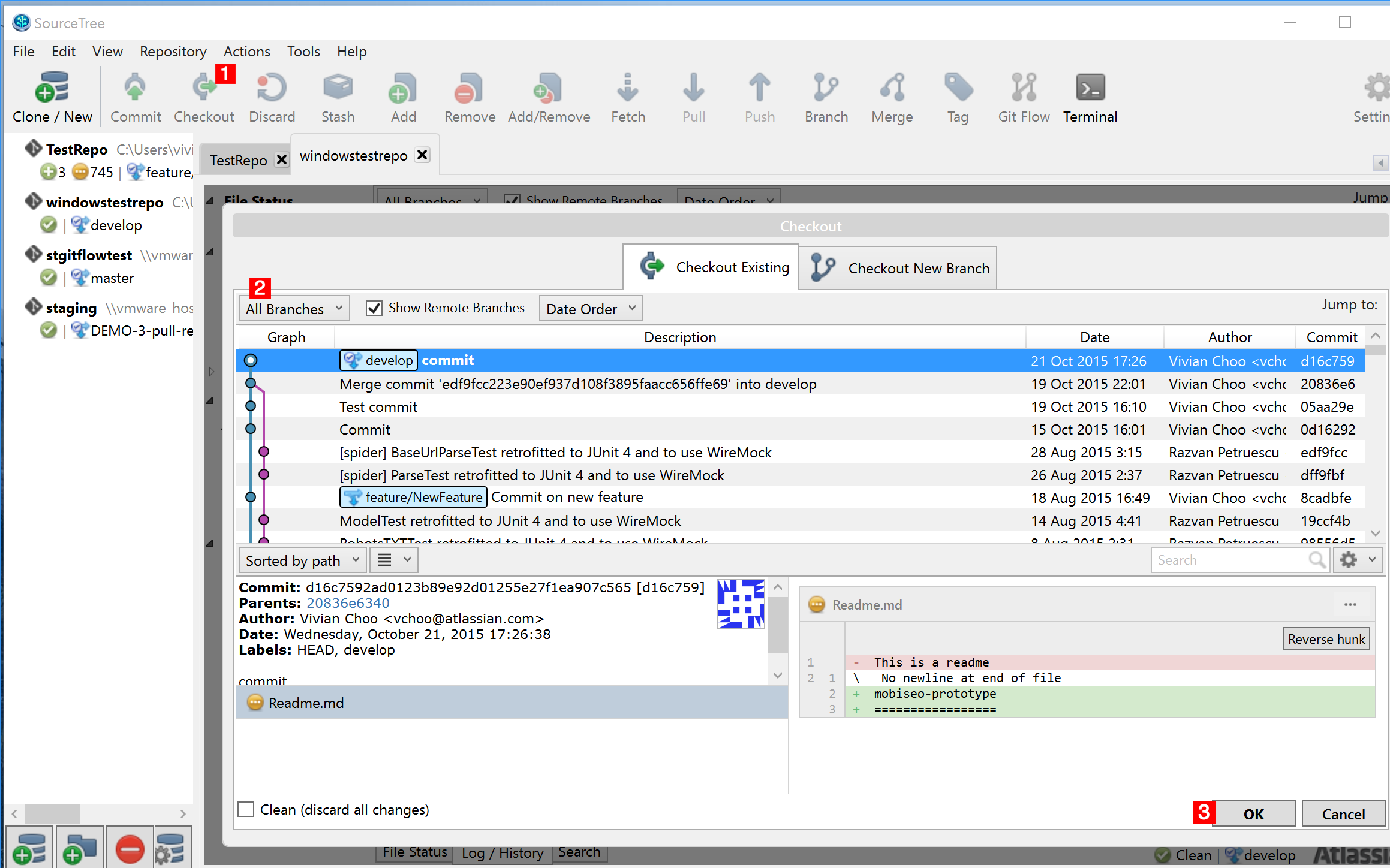

Even the things I call remote-tracking names, such as origin/develop, are local to your Git repository. The tricky thing here is that all branches are, literally, local to your own Git repository. If you want to do your own development, you need a (local) branch. This detached-HEAD mode makes sense if you merely want to look at that particular commit, and maybe even build a release from it, but not make any modifications. But if you like, you can go ahead and use the detached-HEAD mode using either: git checkout origin/develop A better message might be, e.g.: Created new branch 'develop', with its upstreamĪgain, as in matt's answer, this is almost certainly what you want to use. So Git should probably not use it at all. What does remote branch actually mean? Different people will use this pair of words, exactly like this, to mean different things. Git's message here is, I think, confusing to beginners:īranch 'develop' set up to track remote branch 'develop' from 'origin'. As in matt's answer, you literally can't do what you are asking to do.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)